Dongola (Sudan)

Polish Archaeological Mission in Dongola, 2012

Dates: 15 January – 1 March 2012

Team:

Prof. Dr. Włodzimierz Godlewski, mission director, archaeologist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Barbara Czaja-Szewczak, textile conservator (Museum Palace in Wilanów)

Katarzyna Danys–Lasek, archeologist/documentalist (PCMA UW scholarship holder)

Prof. Adam Łajtar, epigraphist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Robert Mahler, anthropologist (PCMA UW)

Szymon Maślak, archeologist (PCMA UW)

Dorota Moryto-Naumiuk, wall painting conservator (Academy of Fine Arts, Kraków)

Dr. Marta Osypińska, archeozoologist (Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poznań)

Dr. Dobrochna Zielińska, archeologist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Ajab Said el-Ajab, archeologist, NCAM inspector

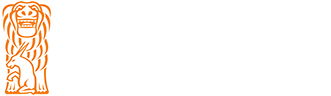

Excavation and conservation work in 2012 were carried out in the Citadel (royal building complex B.I and B.V), Kom H (Northwest Annex and monastic church) and the so-called Mosque Building (Throne Hall).

Citadel: Building I – Palace of King Ioannes

Storerooms B.I.37, B.I.40–41 were explored in the western part of the building as was the vestibule of the northern palace entrance (B.I.24) [Fig. 1].

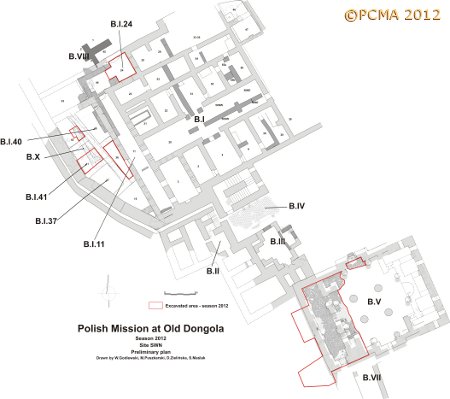

The southern part of B.I.37 was cleared down to the original floor level, discovering a passage in the east wall opening into corridor B.I.11. This entrance was blocked at some point, creating a conveniently isolated space for dumping palace rubbish. Rubble from the destruction of the building in the end of the 13th century comprised the upper part of the fill inside this room. Continued exploration of rooms B.I.40–41 down to the foundation level of the outer, west citadel wall cleared remains of mud-brick architecture preceding the raising of the Palace of Ioannes. Pottery found in context with these building remains dates the construction to the mid 6th century [Figs 2-3].

Alterations of the western part of the palace in the early period, in the 7th-8th century, were traced in the two rooms. The architecture between the palace (B.I.11) and the west wall of the citadel was rebuilt at least twice. The fill of the two rooms contained a large assemblage of pottery, both locally made and imported from the north, mainly Egyptian amphorae, but also vessels from Palestine and North Africa, delivering wine to the palace in the end of the 6th and the first half of the 7th century. Jar stoppers were a common accompanying find. Numerous fragments of animal bones, undoubtedly leftovers from the palace tables, were also found in the fill. Well clarified green glass, chipped from chunks used for glass-making in secondary production workshops, can be considered as proof of glass ateliers operating in the vicinity of the palatial complex. Small fragments of glass products were also recorded.

Clearing of the western part of the late 13th century rubble filling room B.I.24 revealed the full size of the northern entrance with monumental arcade (H. 3.40 m; W. 2.53 m), blocked in the end of the 13th century [Fig. 4], and the original walking level inside the vestibule. A canine graffito was preserved on the south wall [Fig. 5]. A single doorway under a stone arcade led from the north vestibule to the palace corridor (B.I.11).

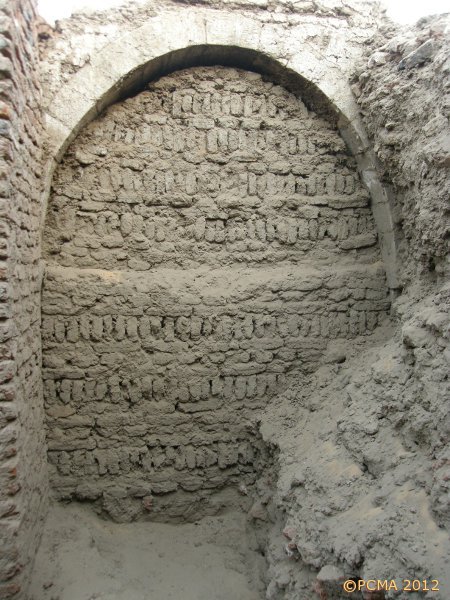

Citadel: Building V

Excavations in the western and northwestern part of this substantial church building associated with the palace (B.I.) uncovered the robbed out west wall and western part of the north wall. The stone blocks from this part of the structure were salvaged sometime in the 19th and 20th century, but the walls in the southern and eastern parts of the building still rise to a height of 3.60 m. The floor in the narthex and the northwestern part of the naos was made of broken sandstone slabs. The narthex was a narrow space filling the whole width of the building, separated from the naos by a wall with three doorways under stone arcades. It was entered from the south, through a doorway faced with sandstone blocks, well dressed and with sharp edges. Another entrance led directly into the building through a central doorway installed in the north wall. The walls of the narthex were coated with lime plaster; fragmentary wall paintings have been preserved on these walls.

A staircase in the southwestern part of the naos was accessible from the naos as well as from the narthex, being located just inside the southern of the three passages between the naos and narthex. The middle one of the three passages preserved a renovated stone pavement and in it a Greek funerary stela made of local marble, dedicated to one Staurosani, grandchild of Makurian King Zacharias; this member of the royal family of unidentified sex died on 22 December 1057 [Fig. 6].

The stela bears a popular prayer of the Euchologion Mega type but without the phrase ensuring that the soul of the dead rests in the bosom of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. It also attests the existence of a previously unknown ruler of Makuria designated as Zacharias V, grandfather of Starosania, who was presumably the last king of the Dongolan dynasty (836–1060). The name of the dead individual, most probably a woman (or girl), has not been attested before and the stele brings no information about the offices filled by the person whom it commemorated. Neither has the age of the person, who may have been a child, been preserved. The missing name of the father, doubtless a member of the royal family, is also intriguing.

From the technological point of view, building B.V is evidently among the best constructions discovered so far in Dongola. The founding date has not been determined as yet, but it surely had place before the end of the 9th century.

Monastery of Great Anthony (Kom H): Church

The monastery church, excavated in 2005-2007 by Daniel Gazda, was cleared again in 2011 in order to complete the documentation of the interior and to carry out additional research. The church follows the plan of a three-aisled basilica with central tower and was erected in the second half of the 6th century. This season the documentation of the pavement inside the church was completed [Fig. 7] and test pits were explored in the central and eastern parts of the church, in the pastophories and sanctuary. The foundation footing of the dividing wall between the nave and northern aisle in the naos, bearing the stone pillars of the central tower and granite columns, was traced.

Mausoleum of St Anna-by

Additional documentation was completed inside the sanctuary of the Makurian saint Anna-by, which was attached to the western façade of the monastery church in its southern end. The wall paintings in the sanctuary were documented in full, discovering more images in the process [Fig. 8]. The grave of the saint, a narrow trench excavated 1.60 m deep into the relatively soft bedrock, was uncovered again in order to subject the skeleton to anthropological examination. The man buried proved to have been aged about 50-60 years at death and to have suffered probably from the DISH (Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis) syndrome, which is manifested among others by one-sided ossification of the ligaments within the backbone, which would have resulted in considerable reduction of its flexibility.

Mausoleum of the Dongola bishops

Research was continued in the northern part of the Northwest annex, which appears to have been attached to the monastery tower in the 11th century. The northern crypt (no. 3) was reopened in order to carry out an anthropological examination of the bones and to complete the architectural documentation of the crypt. The exploration was made very difficult by the character of the fill inside the crypt: a solid mass formed by the collapsed plaster of the walls and vault. The northern crypt was erected in a large trench together with the southern one (no. 2) as a single building event. Its walls were made of red brick, the vault of mud brick. The vault was supported in the southern part on the vault of crypt 2, indicating that it was built second. Access to both of the crypts was through two narrow (35 cm) separate shafts situated on the western side, ending in small vaulted entrances in the west wall of the burial chamber. The entrance to crypt 2 measured: H. 54 cm; W. 36 cm. The burial chamber was 245 cm long, 98–100 cm wide and 105 cm high. It contained the bodily remains of five individuals laid to rest in two layers, which were separated one from the other [Fig. 9]. In the bottom layer, two of the bodies had been pushed to the side next to the north wall in order to make room for a third corpse, which was found in undisturbed position. The two bodies in the upper layer were buried at a definitely later date. These last burials preserved some fragments of color-dyed robes of wool and silk and a fragment of a silk shroud decorated with fine thin stripes of red, dark blue, cream, brown and green. All the skeletons were identified as male. The age of the deceased was determined provisionally as about 50+. The sole equipment still found inside the crypt was the bottom part of a late, locally made amphora. A few dozen small potsherds must have entered the fill together with the part of the chamber vaulting which had collapsed into the crypt as some point in its existence before the later set of burials.

Mosque: Throne Hall of the Makurian Kings

Conservation work was continued by a Polish-Sudanese team in the central hall of the upper floor of the building of a mosque, which had been until 1317 the Throne Hall of the kings of Makuria. Fragmentarily preserved paintings on the north wall, on either side of the entrance, were cleared, as well as small fragments of wall paintings surviving in the southeastern corner of the hall. After cleaning this seasons, the remains of an already recognized painting of a Cross with the four apocalyptical beings and a central bust of Christ on the north wall to the west of the entrance were found to be a much more complicated composition than believed so far [Fig. 10]. The cross with five tondos — a central one with a representation of Christ and four with the apocalyptical beings on the arms — stood centrally at the top of a set of steps. Flanking the cross at the base is a series of white-robed enthroned figures, the exact number of which is difficult to ascertain due to the poor state of preservation of the wall plaster. These were most likely wise men (elders) and there should be 24 of them, twelve each on either side. On the two sides of the base of the cross there are other fragmentary figures, presumably adoring the cross. The composition would therefore be unique in Nubian painting, referring to the text of the Revelation of St John and a text attributed to Cyril of Jerusalem, a fragment of which, translated into the Old Nubian language, was found at Qasr Ibrim in 1982. It reads:

“… when the four (living creatures)give glory, honor and thanksgiving, the twenty-four white, glorious priests, when they take off their crowns, worship the throne … ” (transl. M. Browne)

It is difficult to identify the figures on either side of the cross. One of them wears a partly preserved crown.

[Text: W. Godlewski]