Dongola (Sudan)

Dates: 4 January – 17 February 2010

Team:

Prof. Dr. Włodzimierz Godlewski, mission director (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Prof. Dr. Adam Łajtar, epigraphist, Greek and Old Nubian texts (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Katarzyna Danys, ceramologist and documentalist (freelance)

Robert Mahler, anthropologist (PCMA)

Szymon Maślak, archaeologist (freelance)

Dr. Artur Obłuski, archaeologist (freelance)

Bartosz Wojciechowski, archaeologist and topographer (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Dr. Teresa Kaczor, architect (University of Technology, Wrocław)

Dr. Marta Osypińska, archeozoologist (Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poznań)

Amal Mohamed Ahmed, inspector (NCAM)

In 2010 the Dongola project continued excavations of the royal architectural complex found on the city’s citadel (B.I and B.V), the commercial building on the citadel (B.VI) and in the monastery located on Kom H (hermitage of St. Anna and anthropological studies of the material from Crypt 2). The topographical survey of the town progressed in preparation for a site presentation project to be prepared by Dr. Teresa Kaczor, which is aimed at opening the entire archaeological site to visitors. Prof. Adam Łajtar continued his studies of the Greek and Old Nubian texts and Dr. Marta Osypińska examined an assemblage of more than 4,000 animal bones which had been found in the stores of the Palace of Ioannes as well as some post-Makurian houses excavated on the Citadel.

Archaeological investigations of the town which was the capital of the Kingdom of Makuria foster a better understanding of the biggest African state that existed from the 6th through the 14th century (corresponding to the medieval period in Europe). It is noteworthy that for more than 500 years Makuria managed peaceful relations with the Arab caliphate while maintaining very strong ties with Byzantine culture and upholding Greek as an official language of the kingdom, not to mention traditions from before the age of iconoclasm in Constantinople.

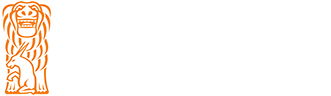

The seat of royal authority on the Dongolan Citadel dates back to the founding of the city in the late 5th and early 6th century AD when the massive fortifications were first constructed. Archaeological research continued to focus on a complex of royal buildings in its southwestern part and on Building VI situated in the vicinity of the river harbor at the northwestern end.

The palace of King Ioannes was a building with a floor area of more than 1200 square meters. The ground floor of the structure (which had an upper storey) comprised two sections separated by a long corridor. The western section was of evidently domestic character; it has suffered much more extensively from slope erosion in this part of the hill, facilitating in effect testing of building chronology. Excavations here were geared to establishing when the palace was built and, in view of the character of the finds, what kind of trade relations the residents of the palace upheld with the Mediterranean, that is, Byzantine world in the 6th and early 7th centuries.

A rich deposit of pottery, glass and metal uncovered in the units in the western part of the palace (B.I.15; 37; 40; 42) provided dating evidence for the founding of the structure in the last two decades of the 6th century, which is substantially earlier than the previously suggested dating in the first half of the 7th century. A numerous assemblage of imported amphorae, identified as coming from the Aswan region, the Mareotis and Middle Egypt, with isolated examples from Palestine, Syria and the Greek islands, helped to date the founding of the palace; primarily, however, it has revised our view of the trade between Dongola and Egypt and the Byzantine Empire as a whole. Documented so well for the first time, this important discovery has also helped to redefine the later relations between the Kingdom of Makuria and the Caliphate determined by the baqt, the political and economic treaty of 651 guaranteeing Makuria’s independence and establishing the northern border with Egypt in the Aswan region, as well as determining a package of goods for bilateral exchange. This pact, signed at Dongola and unprecedented in its time, appears today as a natural continuation of a similar treaty (Pactum) concluded between Makuria and Byzantium in the last decade of the 6th century. The countless Egyptian and Palestinian amphorae from the late 6th century found in the royal palace at Dongola are testimony to the existence of such a treaty.

Exploration of the western part of the vestibule leading inside the palace (B.I.44), rebuilt a number of times and ultimately filled with rubble, uncovered the stone arcade of the entrance to the main corridor of the palace (B.I.11).

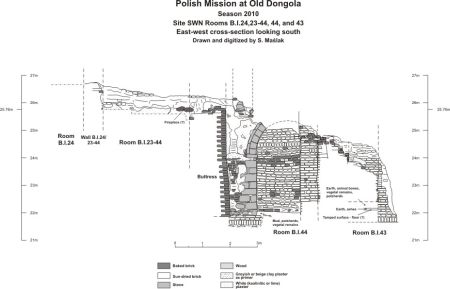

The vestibule was rebuilt during the time of the wars with the Egyptian Mamluks (last quarter of the 13th century). The rubble here yielded an extraordinary inscription in Old Nubian recording the work of an anonymous potter (manufacturer of amphoras?).

South of the palace on the citadel there stands a sacral building (B.V, 21 x 15 m in plan and with walls standing 4 m high) that was part of the royal complex and was already discovered in an earlier season. The eastern part of the building started to be investigated this year in preparation for full clearing next year. The working hypothesis is that this edifice of baked brick with its stone floor pavement and lime-plastered walls covered with murals was the main church of the royal complex on the citadel. It definitely appears to be the best built structure in Dongola, following a central plan with a dome supported on four central pillars. This architectural plan was introduced in Dongola as an original idea of Dongolan architects in the middle of the 9th century. The Pillar Church discovered in 1995 on a platform by the northwestern tower of the fortifications is an excellent example of this kind of plan. It is very likely that the royal palace church was the first edifice of its kind erected in Dongola. The murals already uncovered in a test excavated in the structure, on the naos and pillars of the church walls, were executed on lime plaster which is the only known instance of such plaster in Nubian painting. It is noteworthy that the Faras wall paintings of the 8th as well as 10th century were all painted on a coating of lime whitewash applied on mud plaster.

Another building excavated completely this year has a plan unparalleled in the architecture of the Kingdom of Makuria. It is a large building located in the northwestern part of the Citadel. It is erected of mud brick and is composed of a central hall with six round pillars and rows of narrow rooms laid out symmetrically on the eastern and western sides. The south side is occupied by a set of similarly narrow rooms and an entrance vestibule. Unfortunately, the northern side of the building was completely destroyed. The structure was erected in the 12th century on the ruins of earlier architecture which has yet to be explored and identified. The interpretation of Building VI and its furnishings, as well as the finds from inside it, is not fully documented yet and hence not clear. It could have been a storehouse, an interpretation which is suggested by the many narrow rooms, the location of the building near a river harbor and analogous layout of Meroitic buildings referred to as palaces, which were erected from the 1st century BC through the 3rd century AD. Such structures are known from Gebel Barkal, Meroe and Wad Ben Naga.

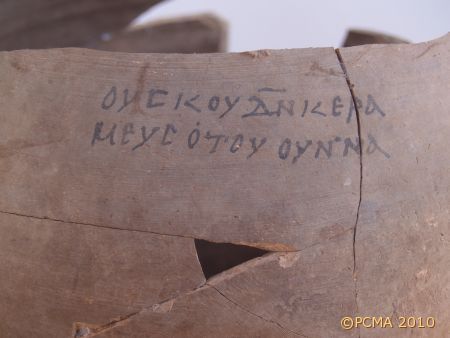

A few houses of the 16th-17th century were cleared in the eastern part of the trench. House H.O9 yielded two magical texts written down in Arabic; one of these was squashed into a small handmade vessel and additionally was pierced with a splinter of wood.

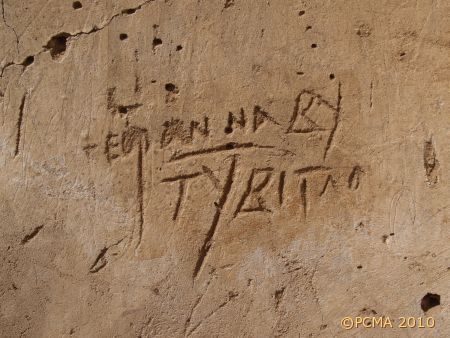

The studies in the monastic compound on Kom H included research on the inscriptions, drawings and murals preserved on the walls of Unit S which was added onto the west wall of the monastery church. Original excavations in 1990 by S. Jakobielski could not identify its original function as the excavation of the monastic complex was still in a preliminary stage. Comprehensive investigation of the architecture and graffiti led to the conclusion that Unit S was originally a small hermitage composed of a monk’s cell and oratory. It was inhabited by a single individual who was most likely not a monk of the Dongolan monastery and who was greatly esteemed in Makurian society for his piety. After his death he was buried in the small oratory and the hermitage as a whole rebuilt into a small sacral building, a kind of mausoleum that remained open to monks and visitors to the monastery alike. Numerous graffiti on the walls of the mausoleum, read by Adam Łajtar, demonstrate that he came to be considered by the local community, but presumably also by the Church of Makuria, as a saint. A few graffiti mention his name as ANNA. In Makuria, the name was both masculine and feminine. One of the graffiti gives what looks like the date of the festival of this saint, the first Makurian saint to be identified in local sources. 10 Tybi (January 6) was at the same time the date of his death. This small building adjoining the monastery church was visited frequently, as indicated by the numerous graffiti on the walls, while the well preserved altar in the old oratory and the liturgical furnishings confirm that saint Anna was venerated until the final abandonment of the Dongolan monastery.

A few drawings, small murals and graffiti representing saints of the Byzantine (Eastern) church — St Menas, St Philotheos and St Theodor Stratelatos killing a serpent, were executed on the original plaster coating the walls of the hermitage. The religious “privacy” of these small icons is beyond doubt and it is admissible that they were made by Anna himself. The presence of St Philotheos could be additional proof that Anna’s road to sainthood was not through the monastic ranks. The other saints in question were not monks either, but suffered a martyr’s death as ordinary soldiers.

W. Godlewski)

[Text: W. Godlewski]