Palmyra (Syria)

47th Season of Excavations — Basilica IV

Dates: 1 October – 4 November 2009

Team:

Prof. Michał Gawlikowski, director (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Dr. Grzegorz Majcherek, co-director (PCMA)

Krystyna Gawlikowska, art historian, ancient glass specialist (freelance)

Karol Juchniewicz, archaeologist (doctoral candidate, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Marcin Wagner, archaeologist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Wojciech Terlikowski, architect (Faculty of Civil Engineering, Warsaw University of Technology)

Aleksandra Trochimowicz, restorer (freelance)

Bartosz Markowski, restorer (freelance)

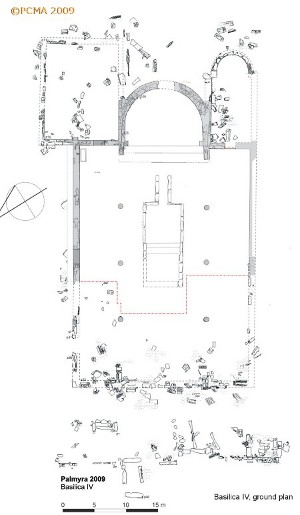

The campaign was a continuation of research initiated in 2007 and continued in 2008, aimed at the examination of a large basilical church (Basilica IV), located in the northwestern part of the city. Previous excavations uncovered a large portion of the northeastern part of the edifice and identified three occupational phases covering the 2nd through 10th centuries AD. The present campaign was wholly geared to excavating the southeastern part of the building, while trying to evaluate the chronological and architectural context of these phases.

Phase I: Pre-church occupation

More of the structure predating the church was now revealed. The construction, featuring a casing wall oriented east-west (top preserved approximately 0.60 m below the church flagging), was built of limestone blocks. The northern side of the wall appeared to be packed with stones and architectural debris set in lime mortar. On the south, a narrow stretch of lime floor adjoined the wall. The whole structure seems to have been planned as a foundation platform for some, as yet unidentified, structure.

The northern wall of the basilica was not structurally bonded with the rest of the church structure, but had been erected probably at an earlier date and only later incorporated into the church complex.

Phase II: Basilica IV – the largest church in Palmyra

Clearing the southeastern part of the church, including its apse, was the main objective this season. Blocks scattered on the surface and those found in the fill were mapped and stored to be used, if the need arose, for a partial anastylosis of the edifice.

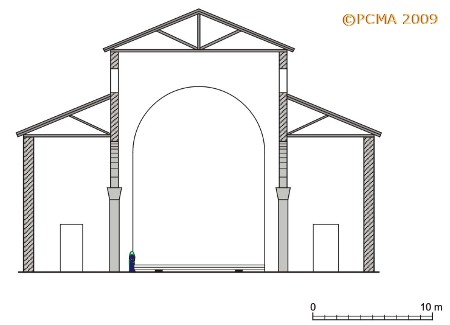

The architectural spolia found in the debris were apparently never considered as decorative material by the church builders. No effort was made to incorporate them in the decorative program of the basilica. As a result, this largest church in Palmyra (for the building details see Palmyra in the 2008 PCMA Newsletter) with its immense flagging and plain stone masonry must have created an air of architectural asceticism.

The original church flagging was made of closely fitted slabs set in lime-ash mortar; some of these slabs were over 2 m long. The half meter difference in levels between the church body and the apse was negotiated by two steps. The sanctuary had apparently been set off by a chancel screen. The only hint of its existence is an incomplete chancel post (1.02 x 0.32 m). It and a few pieces of broken colonnettes and fragments of marble revetment tiles are all that remains of the church decoration. The rectangular bema which was found to occupy the larger part of the nave is a unique feature, especially in this shape, in central Syrian church architecture. A door at the head of the southern aisle led to a martyrium. A grave under the pavement close to the southeastern corner of the aisle contained a few human bones. It was probably a later burial ad sanctos. The walls of the apse, the southern martyrium and a stretch of the southern wall were built of well-dressed limestone blocks laid in isodomic courses.

There is little explicit chronological and stratigraphic evidence on this phase of the building, however Basilica IV has been tentatively recognized as a Justinian-age foundation.

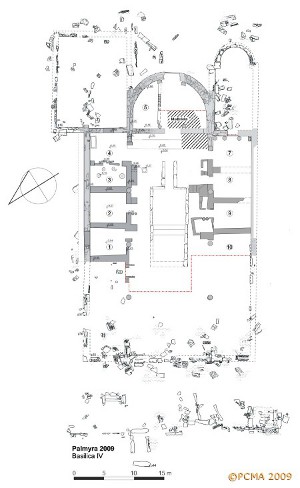

Phase III: Early Islamic structures

The final phase of building occupation corresponds to the Early Islamic age (9th–10th centuries AD); it was preceded by a break in occupation following the abandonment of the church.

The internal arrangement of the building underwent a thorough transformation. The eastern part of the southern aisle excavated this season followed a similar layout as the northern one excavated last year (see Palmyra in the 2008 PCMA Newsletter), yet gave an impression of poorer quality. Intercolumnar spaces were blocked by walls approx. 0.85 m wide. Partition walls subdivided the aisle into a row of regular units (loci 7–10).

Most walls were structured of irregular limestone blocks set in two rows, the space in between filled with mortared rubble, this with the exception of the wall between loci 7 and 8 which was constructed in the pillar technique. No blocks were recognized as belonging to the original church structure. The newly created rooms took up the whole width of the aisle (approximately 6.40 m). They were entered from the courtyard. No installations were found that could help to identify their functions.

In unit 7, two column shafts (approx. 1.50 m tall, 0.70 m in diameter) were set on the church flagging flanking the entrance. Another column was placed in the northern corner, while a pillar was set in the southern one. This arrangement was apparently designed to carry short-spanned vaults. In the same unit, next to the entrance to a former martyrium, a sarcophagus (2.00 x 0.95 m), originally decorated with a row of busts, was found. It may have been set in the martyrium and was later used as a basin or trough.

Similarly to the northern aisle, the wall blocking the intercolumnar spaces was supplemented by abutting piers apparently supporting an outer staircase leading to the second storey. The roofing of the southern wing must have been supported on wooden beams.

After the rearrangement, the apse was separated from the former nave by a 1.20 m tall parapet wall (previously taken for a chancel wall). It was accessed through a 2.65 m wide, pillared and probably arched opening in the wall, flanked by a pair of column shafts. Two walls forming a passage ran towards a columned gateway (approx. 2.20 m wide) pierced at the top of the apse. This gate was framed by doorposts positioned on a wide threshold.

In the southern half of the apse, just below the uppermost layer of rubble, a fallen mud brick wall was cleared. It was made of square bricks (approx. 40-42 cm to a side) bonded in mud mortar. Its western part had most probably fallen from the parapet wall. The eastern section, with diagonally lying bricks, may have come from a collapsed pitched vault covering a passage leading to the entrance.

The exact phasing of the Early Islamic occupation is not clear, but a total re-orientation of the building must have been at the root of the re-planning. The western access was replaced by an eastern gate in the apse, an arrangement which seems to have reflected a change in the urban landscape of Early Islamic Palmyra.

The function of the building is unclear. Its layout, with a central courtyard and rooms grouped around it, the lodging areas on the upper storey and the presence of a large kitchen in the northern aisle indicates an official or administrative function. This impression is enhanced by the monumental gate hall built in the apse. It is therefore tempting to see it as an official residence of a local authority.

In the latest stage of occupation, the building was partly ruined. Some of the units were abandoned while alterations in others point to rather haphazard use.

Two consecutive destruction layers were identified in the area. These have yielded quite a number of dateable finds. The material is surprisingly homogenous chronologically and (apart from a few residual sherds) is all relevant to the Early Islamic period. Several fragments of wheel-made lamps (Palmyrenian group L, 8th–9th century AD) were found together with sherds of brittle-ware cooking pots, locally manufactured coarse ware, steatite vessels and some bone artifacts. The finds included a large repertory of glazed vessel fragments (cobalt blue painted glazes of the “Samarra horizon”), bichrome and monochrome luster ware, lead glazed and sgraffito wares and an example of Chinese celadon. The material corroborates the 9th-10th century as the most plausible date for this phase of the occupation.

[Text based on a report by Grzegorz Majcherek]