Palmyra (Syria), 45th Season of Excavations

Dates: 16 October – 16 November 2007

Team:

Prof. Michał Gawlikowski – director (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Dr. Grzegorz Majcherek – deputy director (PCMA)

Krystyna Gawlikowska – art historian (freelance)

Rania al-Rafidi – inspector (Palmyra Museum)

Dr. Marta Żuchowska – archaeologist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Dr. Dagmara Wielgosz – archaeologist (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven)

Karol Juchniewicz – archaeologist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Marcin Wagner – archaeologist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Wojciech Terlikowski – architect (Faculty of Civil Engineering, Warsaw University of Technology)

Aleksandra Trochimowicz – restorer (freelance)

Bartosz Markowski – restorer (freelance)

Aleksandra Kubiak – student (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Michał Rybak – student (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

The archaeological team continued work in the sanctuary of Allat and probed the little-known Basilica IV, while the restorers were occupied with preparing new exhibits for the Palmyra Museum.

Allat sanctuary: old cistern, unfinished portico and early religious building

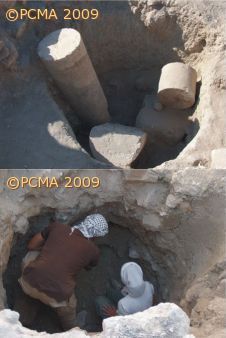

The hole stumbled upon last year near the northwestern corner of the sanctuary turned out upon exploration to be a cistern dug in culturally sterile soil. It measures about 3 m across near the surface, but becomes narrower further down. At a depth of 6 m the bottom had still not been reached. The fill contained a column 4.50 m high, or rather three drums with a base and a plinth but without a capital. Many other architectural fragments and some sculpted pieces dating to the early 1st century AD were thrown into the hole to fill it in. A lot of potsherds, mainly water jugs, from the 3rd century also found their way into the fill.

The evidence, as we read it now, is of a building accident with the column actually sliding into the cistern. The builders must have decided then to fill the rest of the cistern with whatever rubble there was at hand.

This accident seems to have interrupted the construction of the northern colonnaded portico of the sanctuary. Only three column bases from the portico remain in place and there are some column drums lying nearby, but no capitals to match. It seems that even in its heyday the unfinished northern portico looked very much as it does now, after our limited restorations. The aborted construction project appears to have taken place in to the late 3rd or early 4th century AD, when the sanctuary was rebuilt after Aurelian’s sacking of Palmyra in 273.

If this assumption is correct, it follows that there was no northern portico during the first three centuries of the existence of the sanctuary, while the southern and western porticoes, dating from AD 55 and 114 respectively, predate the cella itself.

There is no way at present to establish the date for the introduction of the cistern. A date perhaps even before the sack of Aurelian has been indicated. Firstly, because the cistern lacks proper walls and hence seems unfinished and, secondly, because the builders of the portico appear to have been ignorant of the existence of the feature, considering that they were not aware of the cistern when erecting the column.

But the major discovery of this season was hinted at by some rough stones also found in the fill of the cistern. The stones came from a kind of rectangular platform (4.40 m from east to west by 2.60 m from north to south) which lay right beneath the surface of the sanctuary temenos. It was made entirely of broken stones averaging 30 cm across and bonded in clay. It is noteworthy that no reused stones can be seen in this foundation. The northwestern corner of this foundation collapsed into the cistern, but otherwise its contours have survived intact.

The building that stood on this platform foundation appears to have been razed to the ground when the cella was being built (the temple podium is only 60 cm away from the stone rectangle). On the other hand, the archaic chapel of Allat is only 1.80 m farther away and the back wall of the chapel and the front side of the stone foundation follow the same line. This could suggest some kind of interrelation between the two structures. Was the structure which once stood on the stone foundation another hamana (Aramaic for a kind of chapel), dedicated to a different godhead worshipped alongside Allat, or was it perhaps a monumental altar? There is no means of knowing. It seems to have been roughly contemporary with the archaic chapel of Allat (called hamana in an inscription) dated from the mid 1st century BC. Its destruction could not be dated.

Numerous building blocks and architectural moldings, all of the soft limestone typical of early Palmyrene architecture, were recovered from the cistern pit and from the late walls of the temenos. It is tempting to think that they may have come from the demolished structure.

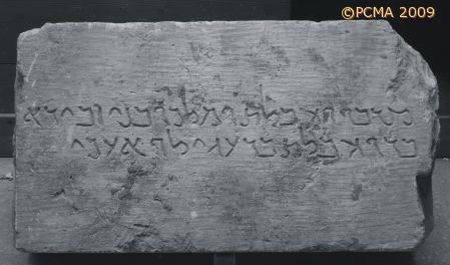

A large block of soft limestone bearing a complete inscription was also lifted from the pit. A similar stone with an identical text was discovered last year in a late wall nearby. The Aramaic inscription reads: “Offered by Wahballat and Malku sons of Zebida son of Wahballat son of ‚Ogeilu A’aki”. The two brothers are already known from five other inscriptions from the sanctuary, referring to their building of the southern portico of the temenos in AD 55.

A sounding in the southwestern corner of the cella proved that there was no symmetry in the oldest layout and no twin monument on the other side of the main chapel. Instead, this trench yielded a corner piece from the back pediment of the cella. It is obvious from the rough upper surface of the stone that it never supported a roof of any kind. This strengthens the evidence that the cella was roofless because of the old chapel it contained and the altar left standing in the middle of the building.

Back to the churches

The sector of the cathedral in the central area of the ancient city has been the object of investigations since 1988. Three churches have been excavated so far, but work was suspended after the discovery of the Odainat mosaic in 2003.

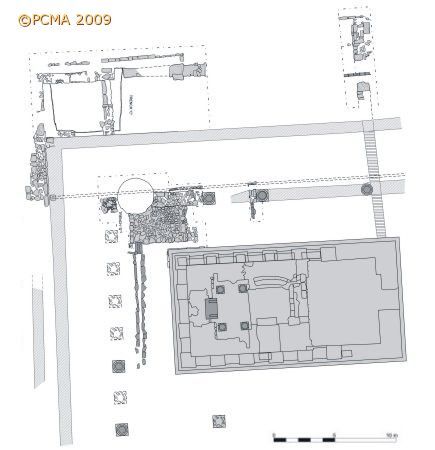

Dr. Grzegorz Majcherek undertook a sounding in the fourth, northernmost church of the episcopal complex. It has been known since the beginning of the 20th century from a plan made by the German expedition to Palmyra.

(Photo M. Gawlikowski)

A trench was traced across the middle of the church nave and it revealed a stone pavement in the aisles. It seems likely that the stone slabs from the nave, at least in the excavated section, had been removed, but even so, the results pointed to the presence of a bema (a raised platform for lectors and singers). If its existence is confirmed, this would be the southernmost example of the feature in all of Syria.

The six still standing columns of the church must have come from earlier buildings. One Corinthian capital remains in place, while another one found in the fill is from a different period. The two unearthed bases are also not assorted. It is not clear how this nave, 13.50 m wide, was roofed, seeing that the columns suppoinged the roof are set so far apart (c. 8.50 m).

Enriching the museum halls

Adding new exhibits to the galleries of the Palmyra Museum has recently become a tradition. In keeping with it, Aleksandra Trochimowicz prepared for display a large sample of Sasanian coins discovered in 2001. A publication of the hoard by the present writer is under preparation.

Bartosz Markowski installed four new sculptures from the Allat sanctuary in the gallery. One of these is the oldest Palmyrene sculpture and certainly the best archaic piece ever found here: a slab representing a panther hunted by an archer on horseback. Another slab featuring a horseman bringing a lamb for sacrifice under his arm, a decorated merlon, and a small relief of veiled women watching a procession of camels, are all early pieces from the Allat sanctuary. In addition, at the request of the Palmyra Museum Director, Markowski installed the lintel of the tomb of Odainat in the inscription room.

[Text: M. Gawlikowski]