Berenike (Egypt)

BERENIKE PROJECT

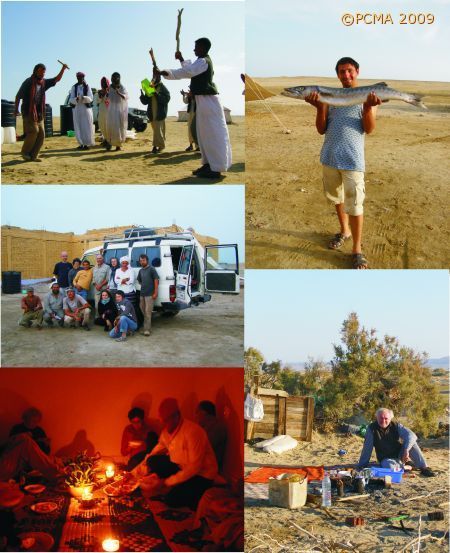

University of Delaware – PCMA expedition

Dates: 25 January – 17 February, 27 February – 1 March 2009

Team:

Co-Directors: Dr. Steven E. Sidebotham (University of Delaware) and Iwona Zych (PCMA, University of Warsaw)

Archaeologists: Shinu Abraham, Joanna Rądkowska, Marek Woźniak, John and Valerie Seeger;

Conservator: Katarzyna Lach

Specialists: Prof. Roger S. Bagnall, papyrologist;

Dr. Roberta Tomber, pottery expert;

Urszula Wicenciak, archaeologist and pottery assistant;

Renata Kucharczyk, glass specialist;

Jarosław Zieliński, archeobotanist;

Paul Cherian, historian

Geophysical team: Tomasz Herbich and Dawid Święch, archaeologist-geophysicists

SCA inspector: Hosam el Dein Aboud Abd Elhamied

The search for the Ptolemaic harbor is on!

With this the Berenike Project returned to the field after an eight year hiatus, now as an American-Polish effort. The beginnings were tense with a skeleton crew sitting in Cairo for weeks before the military permits finally came through. Then it was a hectic 14 days of effective excavation, cramming as much as possible of a whole season’s program into the limited time available.

Ptolemy II Philadelphus founded Berenike as a landing stage for his ambitious project of importing African elephants to be trained for warfare. In the first half of the 3rd century BC these veritable “armored units” were a coveted addition to any satrap’s army. By the time it became obvious to the Ptolemies that African elephants were not suitable for such training and the project was dropped, the Berenike harbor was already in existence and prospering as a fledgling emporium on the Red Sea- India trade route.

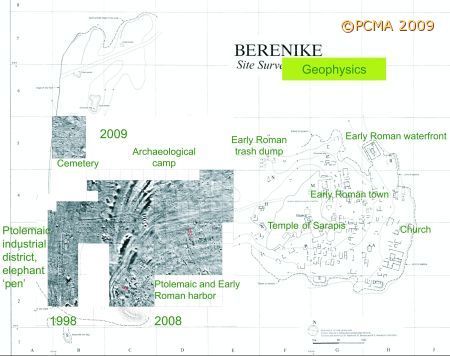

Topographical features on site have long suggested the position of this oldest harbor. Geophysical testing of this crescent-shaped ridge in the southwestern part of the site, started in the previous, largely aborted season in March 2008, confirmed the presence of architecture which could be assumed to be part of the waterfront in this area. Magnetic measurements continued this season, covering an area on the landside of the harbor basin. Again, the results pointed distinctly to an evidently massive and presumably stone-built wharf, but were less positive with regard to any buildings standing on the water edge. The map also presented some curious anomalies fanning out in the part of the site north of the port and east of attested industrial activities. Until some spot testing of these features is completed (for which there was no time this season) it will be difficult to ascertain their exact nature. Their magnitude and unusual shape might indicate a natural land formation of some kind that has thus been imaged on the map. The geophysicists also tested the magnetic method – with good effect – on the site of the 4th-5th century cemetery, where the prospection will be continued in the future.

Bearing in mind the various survey results and hypotheses concerning Ptolemaic and Early Roman urban planning, put forward by archaeologists Joanna Rądkowska and Marek Woźniak, the excavators put in two trenches in the harbor area, both 10 m long and 2.5 m wide. Trench BE09-55 was placed just east of what appears to be the highest point on the crescent-shaped ridge of the harbor in its southwestern part, while BE09-54 was located in the northeastern corner of a topographic feature that is deceptively like the Early Roman harbors of the Eastern Mediterranean (e.g. Caesarea Maritima in Judaea). Both trenches were intended as stratigraphic tests, oriented to cut perpendicularly through the presumed waterfronts and deposits accumulated in the port basin.

Neither trench was concluded in the limited digging time available and it is to be expected that continued work in the coming season will uncover layers and structures connected with the earliest phases of the harbor facilities. Even so, it is now established that the port in whatever form it still had ceased to function in its original capacity probably sometime in the 2nd century AD. The evidence from trench BE09-55 attests to some small-scale manufacturing activities going on in the vicinity, involving processing of stone (beryl, obsidian, carnelian/sard) and shell (mother-of-pearl). Interestingly, the trench also yielded sizable quantities of fragmented mica plates identified by the team’s glass specialist as possibly lapis specularis – windowpanes of Greco-Roman Antiquity. It is tempting to think of the silted-up harbor being used as a ready dump for all kinds of waste, including that from workshop processing of various materials.

In trench BE09-54, excavations provided first of all an explanation for the strongly magnetic anomalies appearing on the geophysical map of the area. There is evidence just under the top layer of drifted sand of presumably spontaneous combustion of organic material, which thus forms lenses of very fine charcoal and ash. This is a process that can be anthropogenic – the Bedouin are known to do it – as well as accidental. Below this the excavators hit upon a poor wall of coral chunks with matting and wooden boards sandwiched between the courses. This wall seems to have been repeatedly reinforced, as if in reaction to a pressing need. South of this structure, inside the presumed port basin, the layers that were reached during this season proved to date to the beginning of the 1st century AD (this is a provisional dating). A large bollard of cedar wood, found very conveniently right in the middle of the trench, stands in confirmation of the area’s prior use as a harbor. It seems, however, in its later phases that this basin was very shallow, admitting only small boats which would have shuttled goods between the ships standing in deeper waters further out and the shore. Knowing the swampy character of beaches around Berenike, it was gratifying to observe the technique by which the ancient stevedores addressed the problem. Lining the ground with tamarisk fascine, they poured the surface with a resinous substance of some kind to waterproof it and make it hard enough for safe walking.

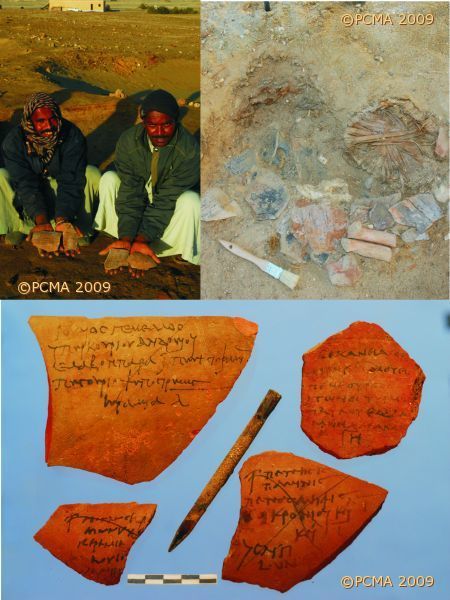

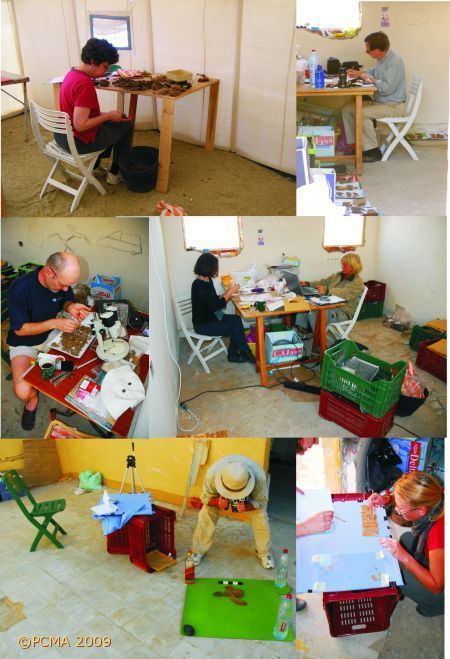

While the search for the port was on, part of the team dug into what is every archaeologist’s dream – a trash dump. This Early Roman dump has already yielded many important and instructive finds in the past and this year was no different. In the very first two days of digging workers brought up more than 200 ostraca – the biggest number ever found at Berenike. This greatly overloaded the understaffed registry and conservation department, but in the end virtually all the finds were recorded and ready for reading when Roger S. Bagnall arrived at the site for a quick 48-hour look at the material. Bagnall brought with him an infra-red camera which his team has been developing for better reading of written documents. It proved useful in a number of difficult-to-read cases.

Apart from the ostraca, the trench yielded the usual array of organic and non-organic artifacts as well as botanical and faunal ecofacts. For the first time the presence of frankincense (Bosweillia sp.) was recorded. Among the glass, which together with the surface collection bore out yet again the sophisticated character of the glassware found at the site, there was an attractive damaged almond-bossed glass beaker.

Meriting interest in the pottery collection were some sherds of jars made in southern Arabia and preserving graffiti, apparently ligatured or monograms, in one of the pre-Islamic south Arabian languages. Another noteworthy find were two blocks of resin from the Syrian fir tree (Abies cilicica), one weighting about 190 g and the other about 339 g, recovered from 1st-century AD contexts in one of the harbor trenches. Produced in areas of greater Syria and Asia Minor, this resin and its oil derivative were used in mummification, as an antiseptic, a diuretic, to treat wrinkles, extract worms and promote hair growth.

In the time available, workers cleaned the area of the temple of Sarapis for photographic documentation. A brief survey was also mounted one Friday to document two new sites in the Eastern Desert: a small one of 5th century AD date which included a dismantled structure, some cairns (into which at least portions of the dismantled structure had been recycled) and a few graves and a second one comprising 60-70 structures and a large circular grave in the center of the settlement. The latter, located close to Kab Marfu’a and dated by the surface sherd collection to the 2nd through 5th century, may have had a related function, that is, a beryl processing center.

This season was sponsored by Dr. John Seeger and Valerie Seeger, Steven Sidebotham, Jean and Thomas Sidebotham, William Whelan, and the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw and its institute in Cairo.

[Text: I. Zych and S. Sidebotham]

For seasons between 1994 and 2001 by the University of Delaware (USA) and Leiden University (the Netherlands), see

http://www.archbase.com/berenike/english1.html