Early Makuria (Sudan)

Early Makuria Research Project: Excavations at El-Zuma Cemetery (three seasons between 2004 and 2009)

Digging dates: first season December 2004–February 2005; second season January–February 2007; third season January–February 2009

Team:

Director: Dr. Mahmoud El-Tayeb archaeologist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw and PCMA)

NCAM representatives:

Nahla Hassan, archaeologist, Antiquities Inspector (first season)

Neamat Mohamed El-Hassan, Antiquities Inspector (second and third season)

Sami Mohamed El-Amin, Antiquities Inspector (second season)

Archaeologists:

Olga Białostocka (Polish Academy of Sciences, PhD candidate)

Ania Błaszczyk (freelance) (second season)

Ewa Czyzewska (PCMA) (third season)

Katarzyna Juszczyk (Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University) (third season)

Hanka Kozinska-Sowa (freelance) (first season)

Artur Obłuski (freelance) (first season)

Małgorzata Wybieralska (freelance) (second season)

Archaeologists-ceramologists:

Urszula Wicenciak (freelance) (first season)

Edyta Klimaszewska-Drabot (freelance) (second and third season)

Archaeologist-photographer:

Kazimierz Kotlewski (freelance) (second season)

Students of archaeology:

Karol Ochnio (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Gamal El-Din Abu-baker (SKAD)

Volunteer:

Miłość Dorsz (Warsaw)

The Early Makuria Research Project was established in 2004 as a joint program between the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology and the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums in Sudan. The idea for the project was proposed by the present author and the work has been implemented and directed jointly with Prof. Włodzimierz Godlewski (University of Warsaw).

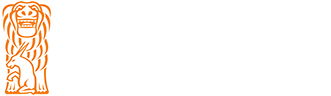

The aim of the project is to study the period between the end of the Meroitic Kingdom and the rise of Christian Makuria as reflected in archaeological sources (cemeteries, settlements and other remains) from the Dongola Reach territory, between the Third and the Fourth Nile Cataracts [see inset map in Fig. 1]. During this transitional period significant changes — political, economic and social — were taking place within the borders of the former Meroitic state. These changes are still controversial and far from being fully understood.

Investigations started with the El-Zuma tumuli field, which has been known since the 19th century when it was visited and recorded by a number of scholars, amongst them Karl Richard Lepsius (K.R. Lepsius, Briefe aus Aegyptien und der Halbinsel des Sinai, Berlin 1852; K. R. Lepsius, Denkmaler aus Agypten und Athiopien, Plates, vol. 12, Berlin 1849-59), Ernest Alfred Wallis Budge (E. A. W. Budge, The Nile. notes for travellers in Egyptian Sudan (12th Edition), London 1912, pp. 866-867) and in recent years by Bogdan Żurawski (B. Żurawski, Survey and Excavations between Old Dongola and Ez-Zuma, Warsaw 2003, pp. 380-381). However, their records are confined to brief accounts and rough sketch plans in addition to ground and aerial photographs of the necropolis [Figs 1, 2].

The village of El-Zuma lies on the right bank of the Nile, about 25 km downstream from Gebel Barkal. Thus, the cemetery under study occupies the higher ground on the western fringes of the village. The site has been subject to continuous plundering and destruction throughout the past centuries. In the last twenty years, the village has grown rapidly due west. Population growth has also resulted in many new extensions of settlement. These developments constitute a direct threat to the existence of the cemetery field as a whole.

There are still about 30 tumuli visible on the ground surface. Their superstructures vary in size and state of preservation. The tumuli are situated in groups on higher ground, separated by watercourses running from the west to the east, towards the river flood plain. The tombs had been classified previously under one category, but closer scrutiny in the field has led to the identification of three types of superstructures. The first type, which is comprised of a group of eight large tumuli, is characterized by a rounded mound of earth and coated with black stones. The diameters of the tumuli range from 25 m to 53 m, whereas the height is between 6 m and 13.5 m. The second type consists of middle-sized flat-top tumuli built of earth and gravel with the body riveted by rough stones. Their diameter ranges between 21 m and 31 m, the height being between 0.80 m and 2 m. The third type is the smallest of all. Tumuli of this type are built of earth and gravel, but without a stone coat or skirt; rows of sandstones on the surface demarcate the mound. The external diameter ranges between 9 m and 20 m, the preserved height not exceeding 0.70 m. It was assumed based on the classification of mound superstructures that the three types would have different substructures as well.

By 2009 three seasons of fieldwork had been conducted. Excavations were concentrated in the first season on verifying the provisional tomb classification. Three tumuli, each representing a different type, were explored, providing an idea of burial construction and the dead buried in them, as well as an estimated date of the cemetery. Further investigations were needed after the first season to confirm or reject the findings, and to add new data specific to burial customs in this particular cemetery. Five more tumuli were explored in the second season of 2007 and another four in the third season of 2009.

Excavations have demonstrated that the largest mounds designated as type I [Fig. 3] relate to a category of burials hitherto known in Nubia only from the Hammur-Abbassyia cemetery in the vicinity of Old Dongola. The grave consists of a vertical shaft of almost square plan measuring 4 m to 5 m square with a kind of pier abutting the east wall, forming a U-shaped plan [Fig. 4].

At the bottom of the shaft there were usually from two to three niches hewn into the sides of the south, west and north walls of the shaft [Fig. 5]. The main burial chamber was located on the south side of the shaft, whereas the other chamber or chambers were dedicated to funerary offerings. The chambers appear to have been interconnected by holes pierced at floor level in the dividing walls. From the back of the main chamber on the south there proceeded to the outside on the southern edge of the mound a long mysterious tunnel [Fig. 5, bottom right]. Two of the tumuli from El-Zuma, T.2 and T.5, featured such tunnels and they are paralleled by two tunnels in tumuli excavated at Hammur-Abbassyia. It remains to be demonstrated whether the tunnels were intentional and if so, what their exact purpose was.

Tumuli of type II with flattened-top mound [Fig. 6], appeared to have a shaft similar to that of type I with the main burial chamber cut in the south side of the shaft, but with no tunnel. Parallel examples to this type were excavated first at Hammur-Abbassyia and recently also at Tanqasi. The construction of these burials and their contents points strongly to a high social rank of their owners. They also testify to cultural continuity in a well organized society.

The last and smallest mounds, type III, represent the simplest kind of burial known from the Dongola Reach [Figs 8, 9]. It consists of a rectangular vertical shaft terminating in a side niche, usually cut into the west wall of the shaft [Fig. 10]. This type bears some elements indicative of continuity of Meroitic burial traditions in the early Makurian period.

All the excavated burials proved to have been rifled in the past. The robbers usually concentrated on the main burial chamber, penetrating it either through a pre-existent tunnel as in the case of our type I or through the tope as in the case of mounds of types II and III. Nonetheless, offerings found in unplundered chambers or forsaken by the robbers comprise a rich collection of different objects. The ceramic assemblage consists of vessels showing inspiration from both Central and Northern Sudan, in addition to a local production [Fig. 11]. Relations and connection between Dongola Reach and Northern Nubia is attested by the existence of imported types of pottery vessels, and some shared funerary rites.

Preliminary studies of burial typology, funerary customs, grave goods and their arrangement have dated the El-Zuma tumuli to the early Makurian period, that is to say, from the second half of the 5th through the mid 6th century AD. Further interpretations should wait for the results of future work on the material, as well as on the site.

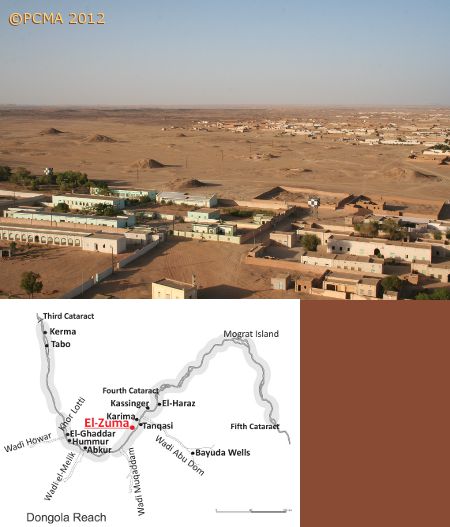

The interest on the part of the local community at El-Zuma has led to a joint project between the NCAM and village elders to create an archaeological park on the site. One of each type of tumulus will be opened to the public. The aim is to encourage tourism and at the same time to raise consciousness among the villagers regarding their local craftwork and other activities based on ethnic societal composition. The project started with awareness-generating meetings and lectures for the villagers, as well as for students of the history and archaeology departments in the Karima Faculty of Arts of Dongola University [Fig. 12]. It should be added that the El-Zuma cemetery is one of four ancient Kushite sites included on the UNESCO list of World Heritage.

[Text: Mahmoud El-Tayeb]