-

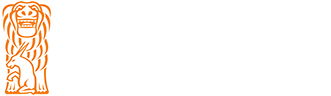

Alexandria, Kom el-Dikka

Theater (4th century AD)/ photo: G. Majcherek

-

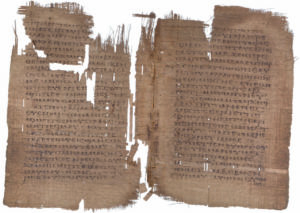

Kom el-Dikka, located in the center of modern Alexandria, is both the biggest and the only archaeological site which allows researchers to study the urban fabric of this ancient city in a wider urban context. The excavations conducted here for more than half a century have led to a better understanding of the city’s past, from topography and architecture to the daily life of its inhabitants, during a very long period: from the 2nd century BC through the 14th century AD.

-

Argishtikhinili

-

The site is located at the top of Surb Davti Blur Hill (Saint David’s Hill) within the village of Nor Armavir (Armavir Province). The settlement was founded most likely around 776 BCE by King Argishti I, as confirmed by a foundation inscription found in the nearby Sardarapat. In Urartian texts, Argishtikhinili is described as a city with extensive economic facilities concentrated along four irrigation canals bringing water from nearby Arax.

-

Bahra 1

A flint arrowhead (ca. 5500–4900 BC)/ photo: A. Oleksiak

-

Bahra 1 is a large settlement from the second half of the 6th millennium BC. During that time, the Ubaid culture was actively developing in southern Mesopotamia, not only expanding to the neighboring regions but reaching as far as Anatolia and the Levant on one side and Iran and the Arabian Gulf coast on the other. Characteristic pottery vessels, often with rich painted decoration, as well as small objects typical of this culture appear on sites along the Gulf coast up to the United Arab Emirates. In Kuwait, they have been first found on the H3 site, a small coastal village located a few kilometers from Bahra 1.

-

Berenike

-

Berenike was founded in the 3rd century BC by Ptolemy II. The king chose this remote location for a fort and a harbor in order to have constant access to African elephants, which were used in battle. The other reason was his fascination with exotic goods and animals. The site lies in a narrow strip of the Egyptian Eastern Desert between the high ridge of the Red Sea Mountains and the Red Sea itself.

-

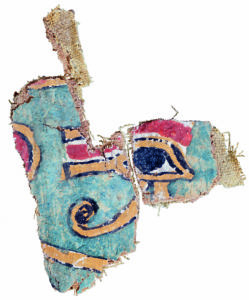

Deir el-Bahari, North Asasif

Udjat eye, cartonnage painting, tomb MMA 509, 22nd dynasty (943 BC–716 BC)/ photo: M. Jawornicki

-

The project aims to document mortuary complexes from the Middle Kingdom and study their reuse in later times, including architectural changes. Its first stage focuses on documenting the architecture as well as collecting and preserving movable objects found in the courtyards. The study of different groups of finds has been carried out since the first season of work. In the 2014/2015 season, the team started conservation work in the grave chamber of Cheti (TT 311) and undertook the reconstruction of the decorated walls of the entrance corridor and the limestone sarcophagus.

-

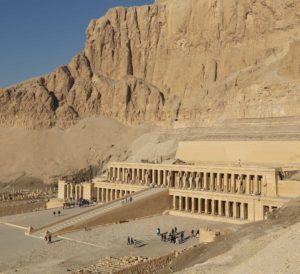

Deir el-Bahari, Temple of Hatshepsut

Temple of Hatshepsut, 18th dynasty, 15th century BC/ photo: PCMA UW

-

The Temple of Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahari, called the “Temple of a Million Years”, was a mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut, a pharaoh of the 18th dynasty. Built in the 15th century BC following the plans of architect Senenmut, it was mostly hewn in the rock. Three cascading terraces ending in porticoes were accessed by ramps erected on the temple’s axis. A vast courtyard closed by a stone wall surrounded the temple. A processional alley flanked by sphinxes with heads of Hatshepsut led to the entrance from the east. The walls of the temple were decorated with scenes from the queen’s life. On the southern side of the Middle Terrace, the Chapel of Hathor was erected, and on the northern, the so-called Lower Chapel of Anubis. On the Upper Terrace were located, among others, the Main Sanctuary of Amun-Re, the Royal Cult Complex, the Solar Cult Complex, and the so-called Upper Chapel of Anubis. Statues of Hatshepsut as Osiris stood against the pillars of the porticoes of the Upper Terrace.

-

El-Detti

Excavations at the El-Detti site, clearing of the shaft of tumulus 1, mid-4th to mid-6th century AD/ photo: A. Kamrowski

-

The site is a vast cemetery from the Early Makuria period with more than 50 recorded tumuli. The majority of them have been destroyed by robbers and modern construction work (leveling of the terrain for road construction). The mission explored seven tumuli in order to examine their construction and compare it to the sepulchral architecture from El-Zuma. Pottery finds and architecture suggest that both sites functioned at roughly the same time.

-

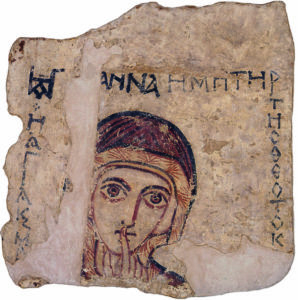

Faras

Wall painting of St. Anne, 7th–14th century AD/ photo: PCMA UW

-

The discovery of the cathedral in Faras with its well-preserved wall paintings was hailed as the “miracle of Faras” by international press. The cathedral complex consists of sacral buildings named after the bishops who founded them: Aetios, Paulos and Petros. Inside the cathedral, the excavators discovered 169 wall paintings executed in tempera on dry plaster. It is the largest collection of Christian Nubian painting ever found, showing its development from the 8th to the 13th century.

-

Gonio – Apsaros

-

Gonio-Apsaros is considered the most important and valuable protected site in Adjara. The well-preserved defensive walls (Late Roman and Byzantine) are a particular attraction for tourists. The most significant discovery from the garrison commander’s house is the mosaic floor, which is not currently accessible to the public. In the future, the best-preserved mosaics will be displayed at the site of the find in a specially built pavilion. Fragments of other mosaics will be displayed in 2024 as part of a new exhibition at a museum in the fortress. Another special find is the so-called Golden Treasure of Gonio. A large collection of accidentally discovered gold objects, dating to the first centuries AD, is available at the Batumi Archaeological Museum.

-

Marina el-Alamein

Pilar funerary monuments, 2nd century BC–6th century AD/ photo: R. Czerner

-

The site of Marina el-Alamein, ancient Leukaspis or Antiphrae, lies on the northern coast of Egypt, about 300 km from the country’s capital and approximately 100 km west of Alexandria. The ruins of the ancient town were discovered by accident in the 1980s during the construction of a tourist resort and a harbor. In the second half of that decade, Egyptian authorities permitted salvage works and then archaeological excavations to be conducted.

The functioning of the ancient city is dated to the Greco-Roman period (2nd century BC–5th/6th century AD). The first phase of research focused on establishing the limits of the site. The town extended for over 1 km from east to west and more than 5 km to the south of the laguna, covering 50 ha. Due to the lack of material for comparison, it is difficult to say whether it was bigger than other sites. The Hellenistic-Roman port town had splendid funerary and domestic architecture.

-

Marea

Corinthian capital/ photo: T. Skrzypiec

-

Marea is an ancient city located to the south-west of Alexandria, on the shore of Lake Mareotis (Maryut). It is known from classical historical sources: Herodotus (II, 30,2), Diodorus Siculus (I, 68) and Thucydides (I, 104). In antiquity, Marea was an important harbor and trading center. It was famous for its excellent wine which was distributed throughout the Mediterranean Basin. The proposed identification of the site as Philoxenite, a city founded by a consul during the reign of the emperor Anastasius (491-518 AD), is still doubtful. It was suggested by Mieczysław Rodziewicz, who based his hypothesis on survey results and the location of the site.

-

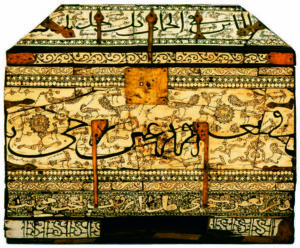

Naqlun

Sicilian casket, 12th/13th century/ photo: W. Jerke

-

The extensive monastic site lies in the south-eastern part of the Fayoum Oasis, at the foot of the Gebel Naqlun and in the valleys between hills. The monastery has functioned in various organizational forms since the middle of the 5th century. It encompasses 90 rock-cut hermitages and buildings of late antique and medieval, as well as modern and contemporary, date.

-

Nea Paphos

Orfeus from the Theseus mosaic floor, 3rd century AD/ photo: M. Jawornicki

-

The site was chosen by Prof. Kazimierz Michałowski in 1963 in response to the invitation from the archaeological authorities of the newly-established Republic of Cyprus (1960). The team uncovered gradually the remains of residential buildings: first the Villa of Theseus, then the House of Aion (since 1983) and since 1986 the insula of the “Hellenistic” House. In 2002–2003 and 2007–2009, intensive archaeological work connected with the building of a protective covering was carried out, but the pavilion was never erected. In 2008–2016, research was conducted mainly in the area of the insula of the “Hellenistic” House. Taking measurements and digitizing the plans was sponsored by the Warsaw Geodetic Enterprise. The mission was also supported by the Society of Enthusiasts of the History of Paphos (Cypriot NGO).

-

Old Dongola

Restoration work on the wall paintings, 6th to the 14th century AD/ photo: D. Szymański

-

Dongola lies on the eastern bank of the Nile, halfway between the Third and Fourth Cataracts. It functioned for more than 1200 years, from the erection of the citadel at the end of the 5th century to the abandonment of the city in the 18th century. It was the capital of the kingdom of Makuria, probably founded by one of its first rulers who built here a city with massive fortifications. Palaces and public building were constructed on the citadel. In the middle of the 6th century, with the conversion of the kingdom to Christianity, the city developed further and extended beyond the area of the citadel. It experienced its heyday in the 9th–11th centuries, but an intensive urbanization process lasted till the 14th century.

-

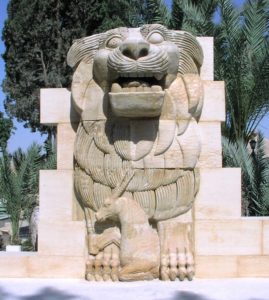

Palmyra

Sculpture of a lion-guard from the temple of Allat, discovered and restored by the PCMA mission, displayed in Palmyra, destroyed in 2015, 1st–4th century AD/ photo: W. Jerke

-

Palmyra was a rich ancient caravan city that lay in an oasis in the middle of the Syrian Desert. Its heyday occurred during the Roman Empire (1st–3rd century AD) thanks to the favorable location on the ancient “Silk Route”, which allowed it to control the lucrative trade between the Mediterranean countries and Persia and the Far East. Palmyra was then a densely populated city with a regular street grid, the impressive Great Colonnade, a monumental arch, a tetrapylon with 16 columns of Aswan granite, an agora surrounded by columns adorned with bronze statues of distinguished citizens, a theatre, baths, and temples: of Nabu, patron of writing and wisdom; of the Arab goddess Allat who was worshipped by nomadic tribes; of Baalshamin, “Lord of Heavens”, and finally the temple of Bel which was the largest and most magnificent building in the city and the symbol of its wealth.

-

Qumayrah Valley

Photo: A. Oleksiak

-

The area of the concession encompasses archaeological remains located along a more-than-10-km-long, L-shaped hollow between massifs forming part of the Jebel Hajar mountain range. The micro-region is called Qumayrah after a village which lies at the junction of two mountain valleys. On the edges of the concession area, there are smaller settlements: Al-Ayn Bani Saidah (in the south) and Bilt (in the east). n 2016, excavations associated with different research clusters began at three sites in the vicinity of the Al-Ayn Bani Saidah village: Early Bronze Age burial site (QA 1), Neolithic campsite (QA 2), as well as Bronze and Iron Age settlement (QA 3). A survey of the valley was also continued.

-

Sheikh Abd el-Qurna

-

Tombs MMA 1151 and 1152 were built in the upper part of the slopes of an unnamed hill behind Sheikh Abd el-Gurna, on the southern side of the so-called Third Valley (also called the Valley of the Last Mentuhotep) where an unfinished royal mortuary complex has been discovered. Its layout resembles that of the mortuary complex of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II in Deir el-Bahari, which suggests that the structure in the Third Valley belonged to one of his successors. High officials built their tombs in the slopes of this valley. The private complexes, as well as the royal one, were never completed.

-

Sijilmassa

Topographic work in the area of sector 3, assumed to have existed from the 8th century to the 16th century AD/ photo: L. de Lellis

-

The name Sijilmassa still conjures images of the oasis and echoes of its former political power and commercial prosperity. As the second Islamic foundation in the Maghreb, the city rapidly ascended to prominence under the Midrarid and Maghrawa rulers. Its strategic location and economic prosperity ensured its significance under subsequent dynasties, including the Almoravids, Almohads, and Merinids. Notably, Sijilmassa served as the birthplace of the Alaouite dynasty. The Moroccan-Polish research project aims to elucidate the multifaceted history of Sijilmassa, encompassing its urban development, historical significance, role in the trans-Saharan trade, and the daily lives of its inhabitants.

-

Soba

Three lanterns found during this research season; many vessels from the storage-kitchen room have similar painted decorations, 5th–16th century AD/ photo: J. Ciesielska

-

One of the medieval Arab travelers described Soba as a city with grand houses and large monasteries, richly-furnished churches and beautiful gardens. It was a multi-ethnic metropolis, the seat of royal and ecclesiastical power. Unfortunately, a lot of time has passed since then, and the city has fell into ruin. In the 19th century, abandoned and ruined buildings of Soba were dismantled, and the bricks were used to build the new capital – Khartoum. In the 20th century, a few archaeologists explored this area, uncovering traces of monumental buildings. They also found extremely interesting, unconventional objects, e.g., a funerary stele of a previously-unknown king David, and objects which reached Soba from the cities of the Mediterranean Basin and the Far East. It is estimated that in its heyday, Soba covered approximately 275 ha. Only 1% of its area has been investigated to date.

-

Tyre

A column of pink granite that adorned the Roman-period temple, found lying on the pavestones of the Roman dromos, overlain by an Ottoman-period wall, 3rd millennium BC/ photo: U. Wicenciak-Núñez

-

The city of Tyre was one of the most significant economic centers of the Mediterranean world throughout much of Antiquity, hence its inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1984. It was for the most part located on an offshore island (originally, on two islands that were conjoined in the 10th century BCE) that could have extended up to 3 km away from the coastline. The island was eventually joined to the shore by a causeway built by Alexander the Great and is now an integral part of the mainland. Five elements defined its urban status in Antiquity: the ramparts, its two harbors, the market place, the royal palace, and the temple of Melkart, the main god of the city. However, most of these elements are known only from written sources, while the available archaeological evidence is very limited. In point of fact, our knowledge is almost completely restricted to glimpses of the Roman and Byzantine remains that are now concentrated in two archaeological parks: at the sites of al-Bass and the Basilicas.